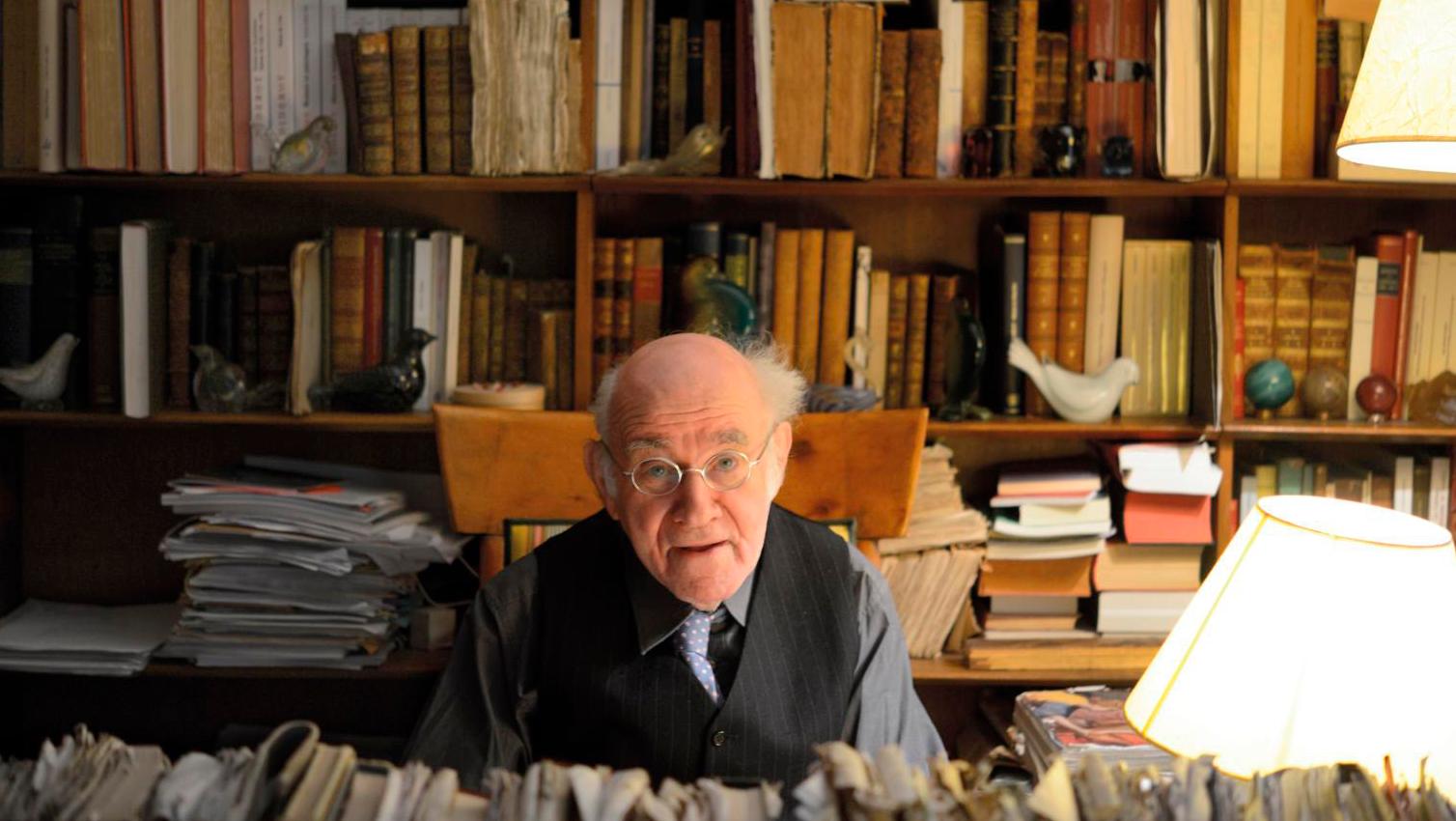

The collections of the leading art historian, which he recently donated to the Hauts-de-Seine département for the future Musée du Grand Siècle in Saint-Cloud, remain as secret as they are astonishing. But the collector now lifts a corner of the veil...

When he speaks in the first person singular, Pierre Rosenberg evokes "the phenomenon of collecting: that 'unpunished vice' as French writer Valery Larbaud described reading," with nonchalant humility. For the Louvre's honorary president and CEO has been collecting since his earliest childhood, and although he no longer owns his collection of bird feathers, he still has his marbles, and stamps at his home in Rue de Vaugirard, Paris. There were also collections he rapidly abandoned, like his stuffed birds. "When I joined the Louvre, collecting was frowned on, but it soon became clear that this didn't hold water." And he cites a long list of curators who donated to French museums, like Michel Laclotte, his predecessor at the head of the Louvre, his younger colleagues Jacques Foucart, Arnauld Brejon de Lavergnée, Jean-Pierre Cuzin and his friend Antoine Schnapper, who taught at Paris IV University. "I often tell the story of a large pastel by Carrier-Belleuse Jacques that Foucart bought at Drouot. But he couldn't afford to pay for its transport, so he carried this naked woman all across Paris on his back. Obviously, a lot of people found this very amusing." On the contrary, dismissing critics who point to a possible conflict of interest between the posts they hold and the museums they serve, Pierre Rosenberg is sad that—to his knowledge—few young curators have taken this path, when they possess so much competence and taste, and could sense what might be in vogue in the coming years. "I believe that collecting is a need for any art historian. You can make mistakes, and I certainly made a few—meaning that you might lose some money or put your faith in a painter who turns out not to be the artist you hoped. So there is a financial risk and even a little aesthetic risk. But collecting brings you into direct contact with works. I think it's enriching for curators to go hunting for acquisitions at Drouot or in flea markets. It makes them humble, because works in a museum are of a completely different quality and importance.…

com.dsi.gazette.Article : 20139

This article is for subscribers only

You still have 85% left to read.