After the sale of part of Yeshwant Rao Holkar II's furniture in 1980, Manik Bagh, the palace he built in Indore in 1930, became a legend. In Paris, Raphaëlle Billé and Louise Curtis have curated an exhibition on one of the last great inter-war patrons: "Moderne Maharajah".

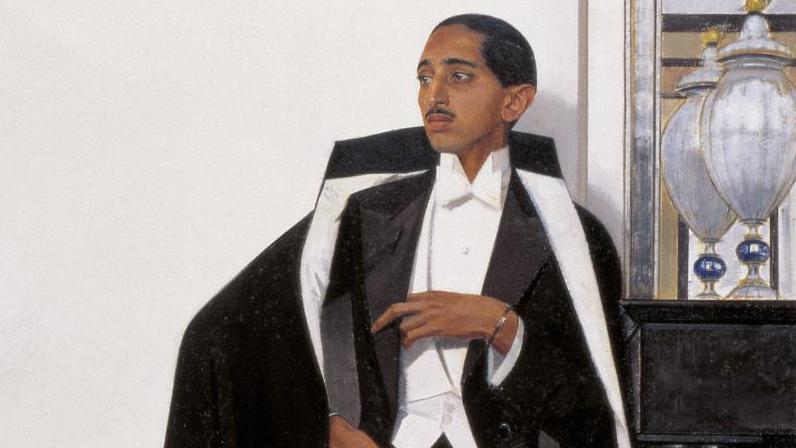

Bernard Boutet de Monvel (1881-1949), S. A. le maharajah d’Indore, 1929, oil on canvas, 194.5 x 116.5 cm, Collection Al Thani.

Merry, elegant, mischievous and enigmatic, the young couple adopt poses that break completely with traditional portraits. Man Ray, who had already celebrated the mysterious charms of modernity with Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles at their house in Hyères, immortalised the new modern couple who had subjugated Paris, New York and finally Hollywood: the Maharajah and Maharanee of Indore. Bernard Boutet de Monvel painted them in Western clothing – him in a suit, her in an evening gown – and the New York smart set flocked to the Wildenstein gallery to admire two new portraits of them in Eastern garb. The prince came to know Boutet de Monvel and Man Ray through the collector, aesthete and writer Henri-Pierre Roché, whom he met at Oxford. Introduced to Brancusi (again by the author of Jules et Jim ), the prince bought his three "Birds in Space" in bronze, black marble and white marble, with the idea of building a temple to contain them. It was also through Roché that the prince…

com.dsi.gazette.Article : 11418

This article is for subscribers only

You still have 85% left to read.