The Kunstmuseum in Basel looks back at the Russian literary icon's visit to the museum in 1867, when Dostoyevsky was dumbstruck by Hans Holbein's Dead Christ. The Idiot is full of references to this masterpiece, whose naturalism was unprecedented in the 16th century.

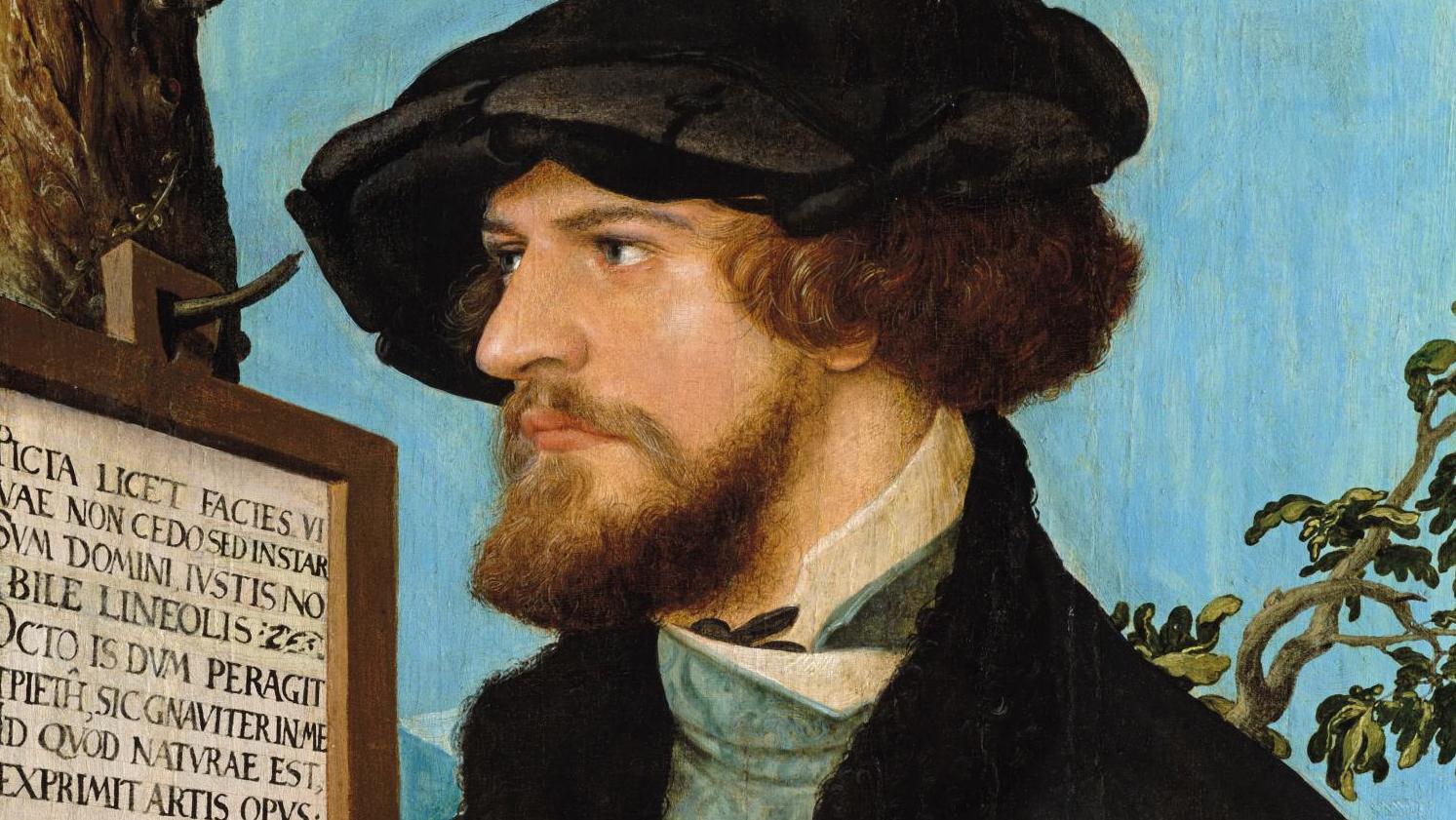

Hans Holbein the Younger, Portrait of Bonifacius Amerbach, 1519, mixed media on panel, 29.9 x 28.3 cm/11.8 x 11.1 in (detail), Basel, Kunstmuseum.

© Kunstmuseum Basel

Bodo Brinkmann, curator of Old Master paintings at the Kunstmuseum in Basel, likes to put fine art and literature into perspective with each other. In 2007, he ended the catalog of an exhibition on Hans Baldung Grien with a study of the themes of sexual frustration and self-portraiture in the work of the artist and the writer Michel Houellebecq. A double jubilee now presents an occasion to confront Hans Holbein the Younger (c. 1497-1543) with Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821-1881), as the former painted his Dead Christ in Basel five centuries ago, and the latter was born in Moscow three hundred years later. When he came across the painting while working on his novel The Idiot , Dostoyevsky succumbed to Stendhal's syndrome and almost had an epileptic fit. This famous episode in the Russian's life confirms the subversive potential of an astonishingly radical work that broke away from the conventional representations of its time. The Dead Christ… Holbein the Younger's name evokes the Italianate canons of beauty found in his legendary Darmstadt Madonna , or his portraits of…

com.dsi.gazette.Article : 30188

This article is for subscribers only

You still have 85% left to read.