The publication of the artist’s complete correspondence sheds light on the depth of his friendships and a personality more sensitive than his reputation suggested.

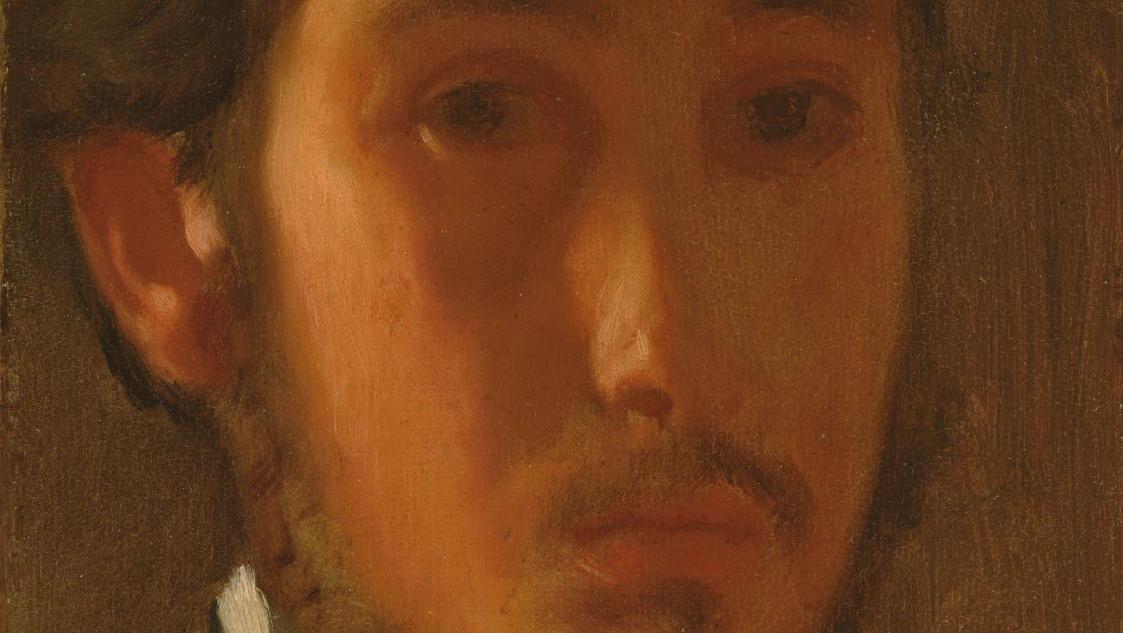

Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Autoportrait au col blanc (Self-portrait with White Collar), c. 1857, oil on paper glued to canvas, 20.5 x 15 cm (8.08 x 5.91 in., detail), Washington, National Gallery of Art.

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

The three-volume publication of Edgar Degas’ complete correspondence considerably increases the body of knowledge about him and the historic context of Impressionism . The 1945 publication of 248 letters, collected by Marcel Guérin, was supplemented by Degas's letters to Tissot in the English edition of 1947. This leap forward is consequential: the number of letters rose from 273 to 1,251. The meticulously prepared edition sheds light on Degas’ key role in forming the group of Independents and organizing its eight exhibitions from 1874 to 1886, as well as the lengths to which he was willing to go to expand the circle and use it to serve his own interests.

Degas was a contemporary of three painters whose correspondence is the most extensive and appreciated: Van Gogh , Gauguin and Pissarro. It contains less about the single, childless private life of Degas than about Pissarro’s life and, from an artistic point of view, is less interesting than the letters by Van Gogh and Gauguin, partly nourished by their isolation and voluntary exile. Degas’s involvement in Parisian social life gives the correspondence…

com.dsi.gazette.Article : 22692

This article is for subscribers only

You still have 85% left to read.