Dinanderie refers to ordinary as well as luxury items made of copper and brass. Since the Middle Ages, the word has encompassed tableware, cookware and many other everyday objects.

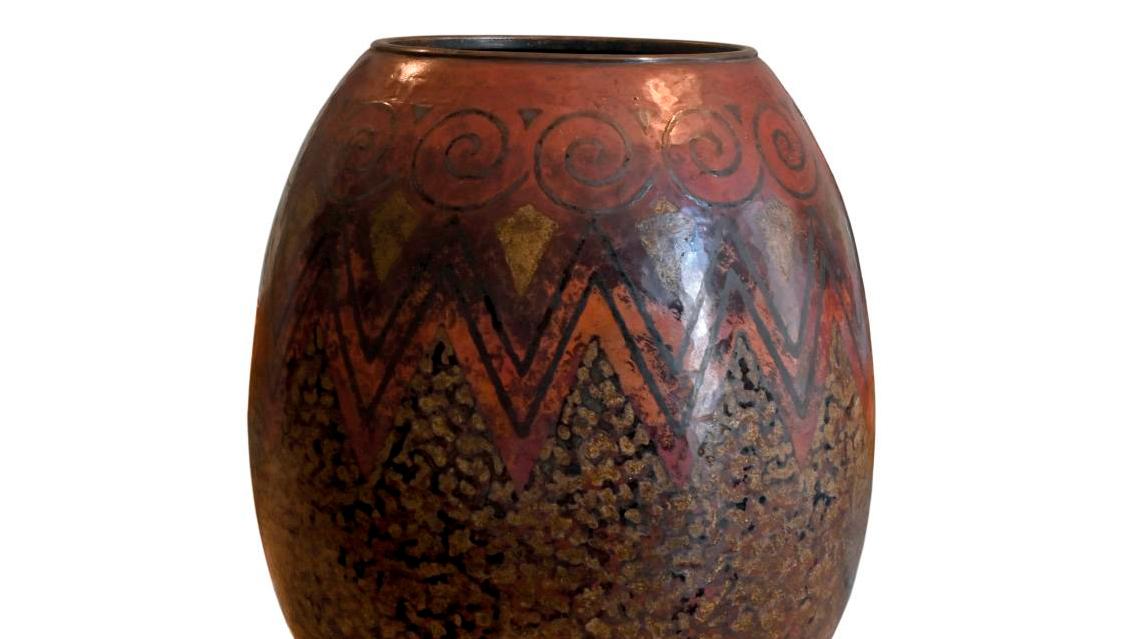

Claudius Linossier (1893–1953), ovoid vase with a light base and wide annular neck, decorated with a “frieze of spirals and a frieze of triple chevrons”, hammered copper proof, signed under the base, 21 cm/8.26 in.

Lyon, January 17, 2021, Bremens-Belleville OVV.

Result: €28,750

Since the fourth millennium BCE, copper, the oldest metal used by man, has been worked and considered a guarantee of prosperity for the areas lucky enough to possess it. However, copper alone is not enough: several factors must come together to transform it. In the 11 th century, the production centers of Bouvignes and Dinant in present-day Belgium’s Meuse Valley were so proficient that dinanderie became the French word for copper and brass craftsmanship. The banks of the Meuse contained large amounts of zinc, a metal indispensable for making brass, and the river provided access to the Hanseatic ports and their economic outlets. In addition, the presence of derle, a type of clay ideal for making crucibles, gave the Meuse Valley a near-monopoly on production in Western…

com.dsi.gazette.Article : 41854

This article is for subscribers only

You still have 85% left to read.