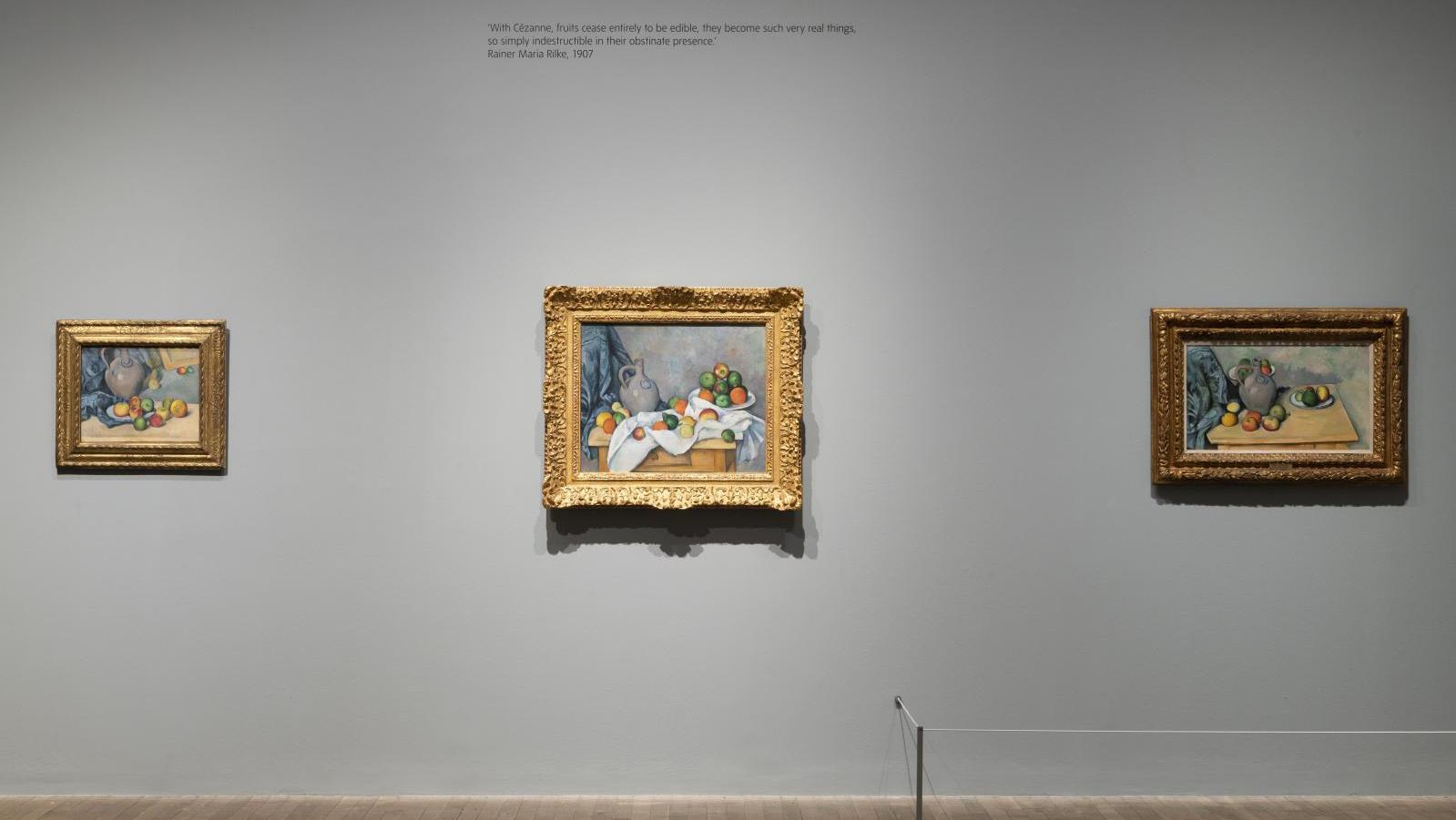

So what’s new, Mr Cézanne? His first retrospective in 30 years, now open at the Tate Modern in London, does not really provide an answer.

With 80 works, the exhibition takes visitors beyond apples and mountains to explore the sexualized violence of his Paris scenes, when Cézanne was still enmeshed in the vision of an "artist's artist", as a precursor of modern art with his pure colors, thick materials and geometric games. Jean-Claude Lebensztejn speaks of a "complex artistic personality, who has been endlessly studied without ever letting himself be totally defined." The exhibition tends to confirm this impression. Removed and disconnected from the show, the catalog mingles…

com.dsi.gazette.Article : 42256

This article is for subscribers only

You still have 85% left to read.